EIN and NHC Event - Time for Action: Human Rights, Democracy, and the Implementation of Judgments of the European Court

/Yesterday, on the 20th of October, EIN co-hosted a briefing with colleagues from the Netherlands Helsinki Committee on the non-implementation of judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), with a particular focus on judgments concerning political persecution. The advocacy event took place in Berlin and was also supported by the Hertie School’s Centre for Fundamental Rights.

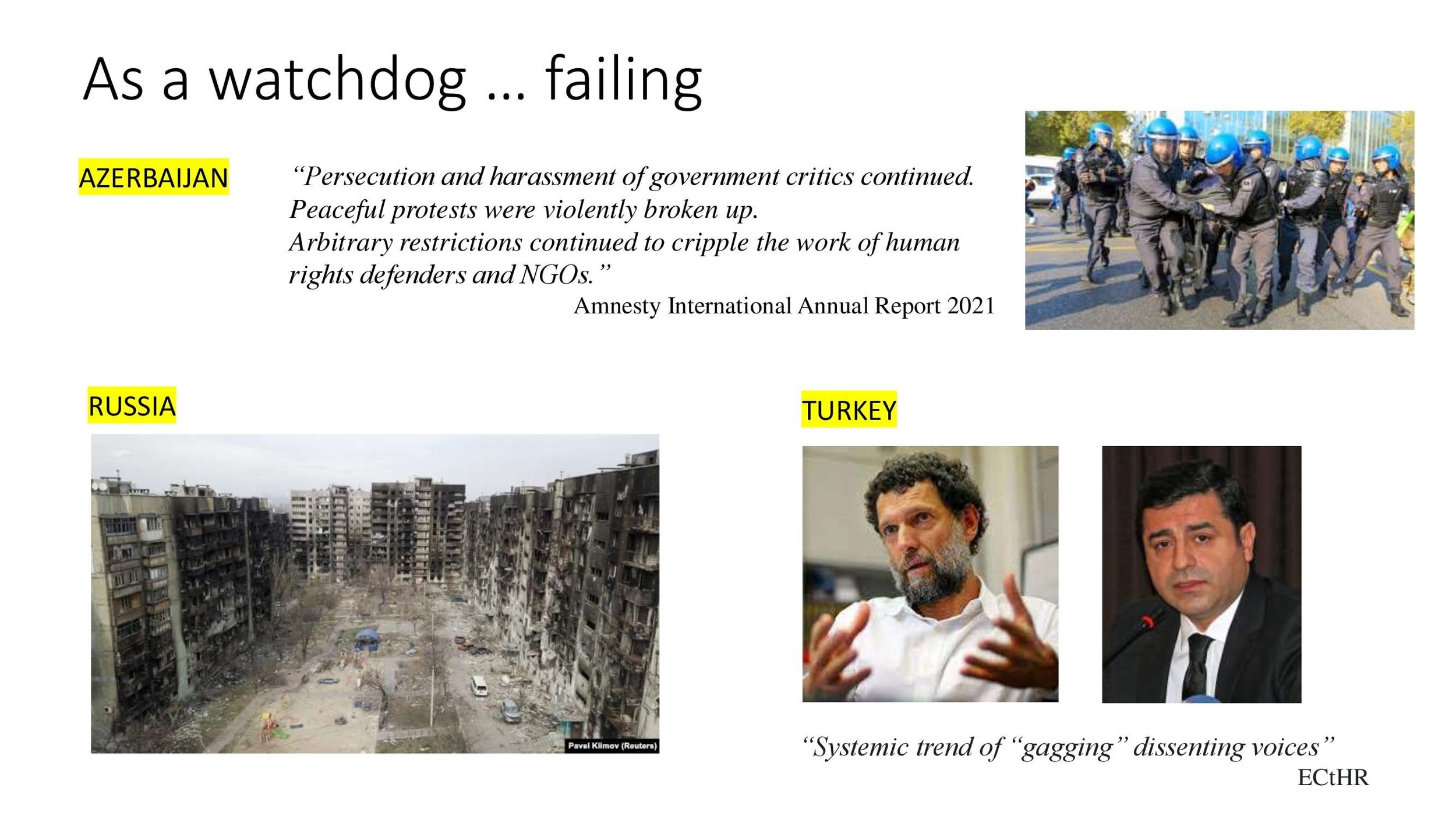

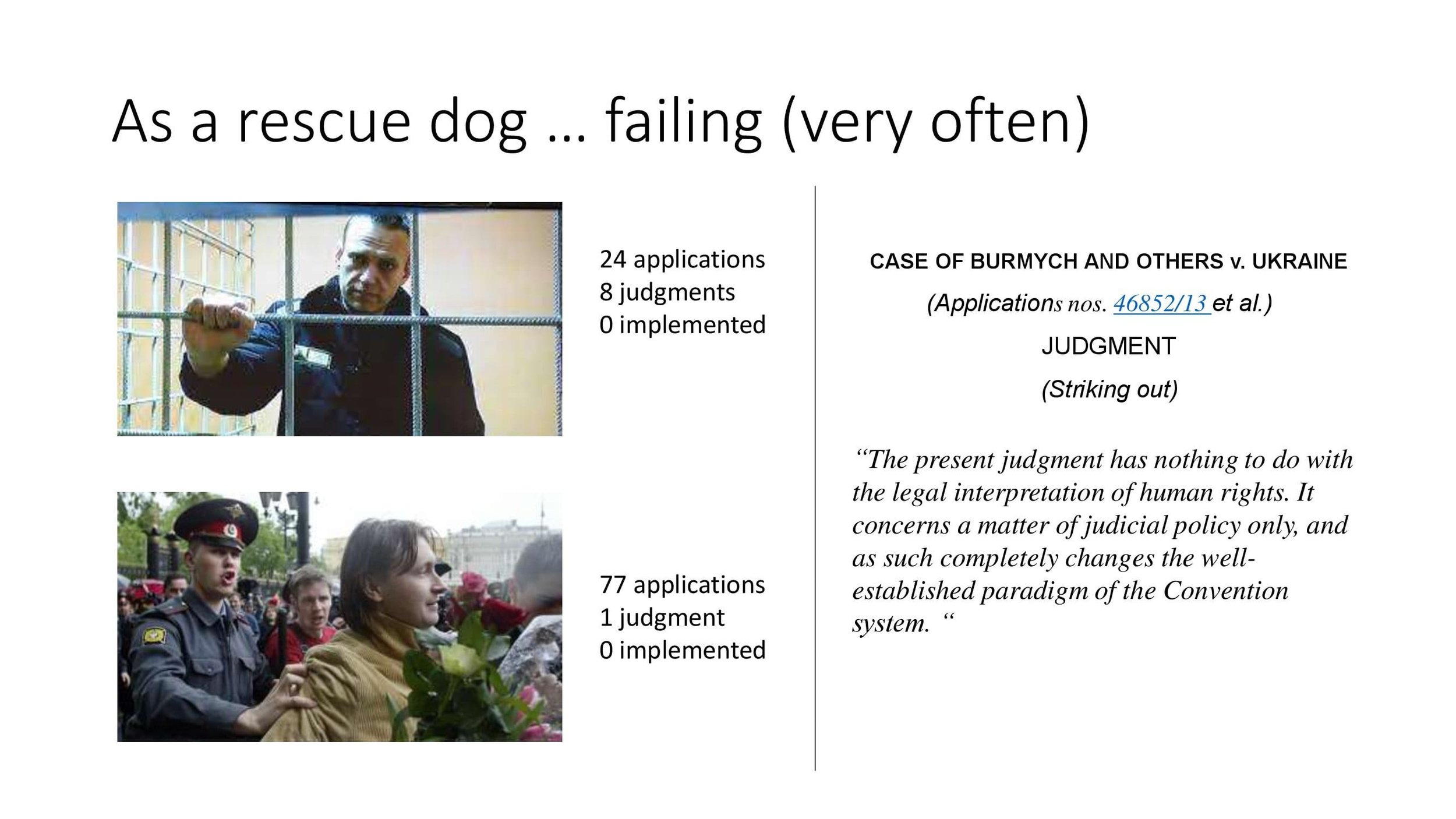

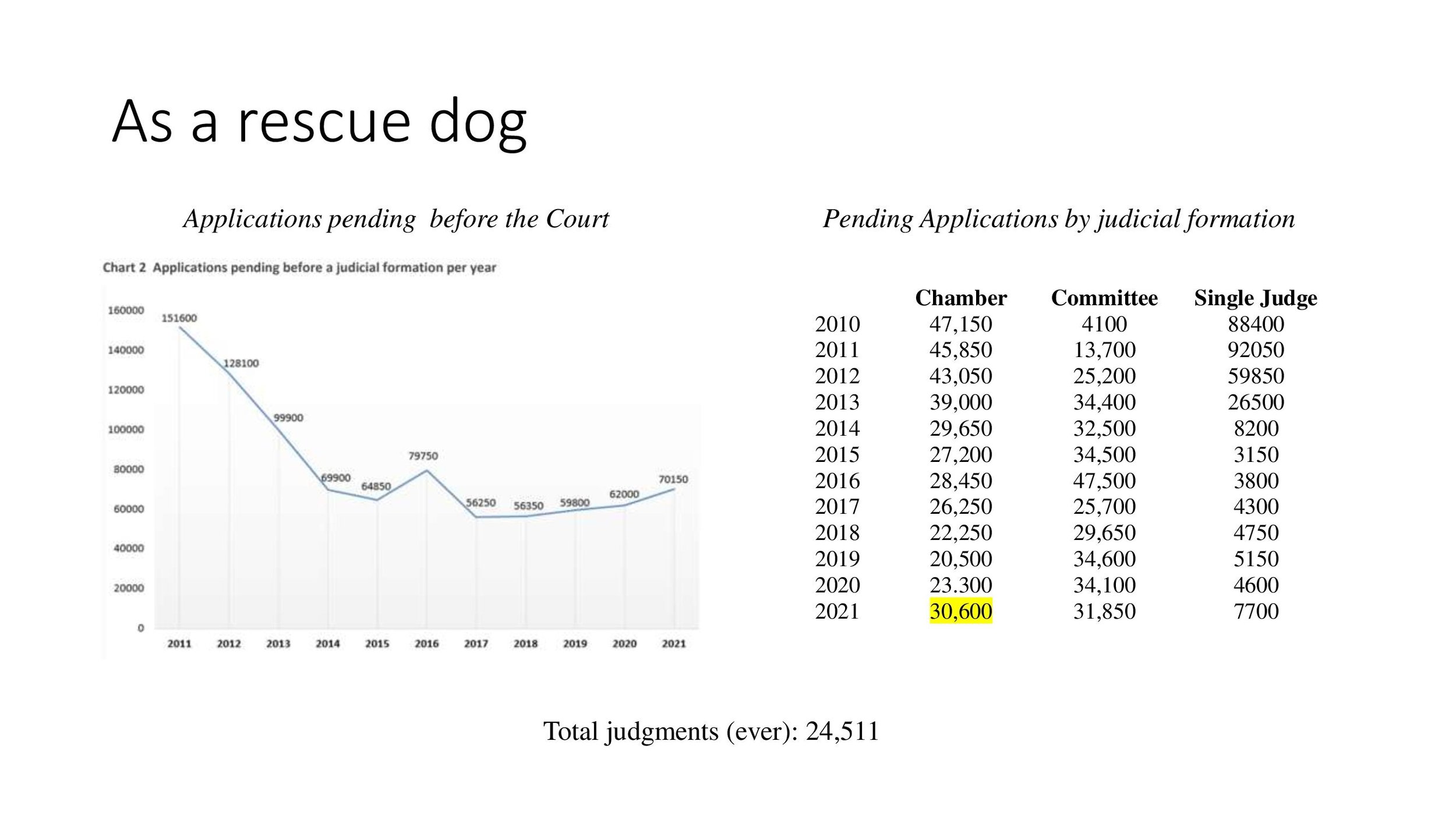

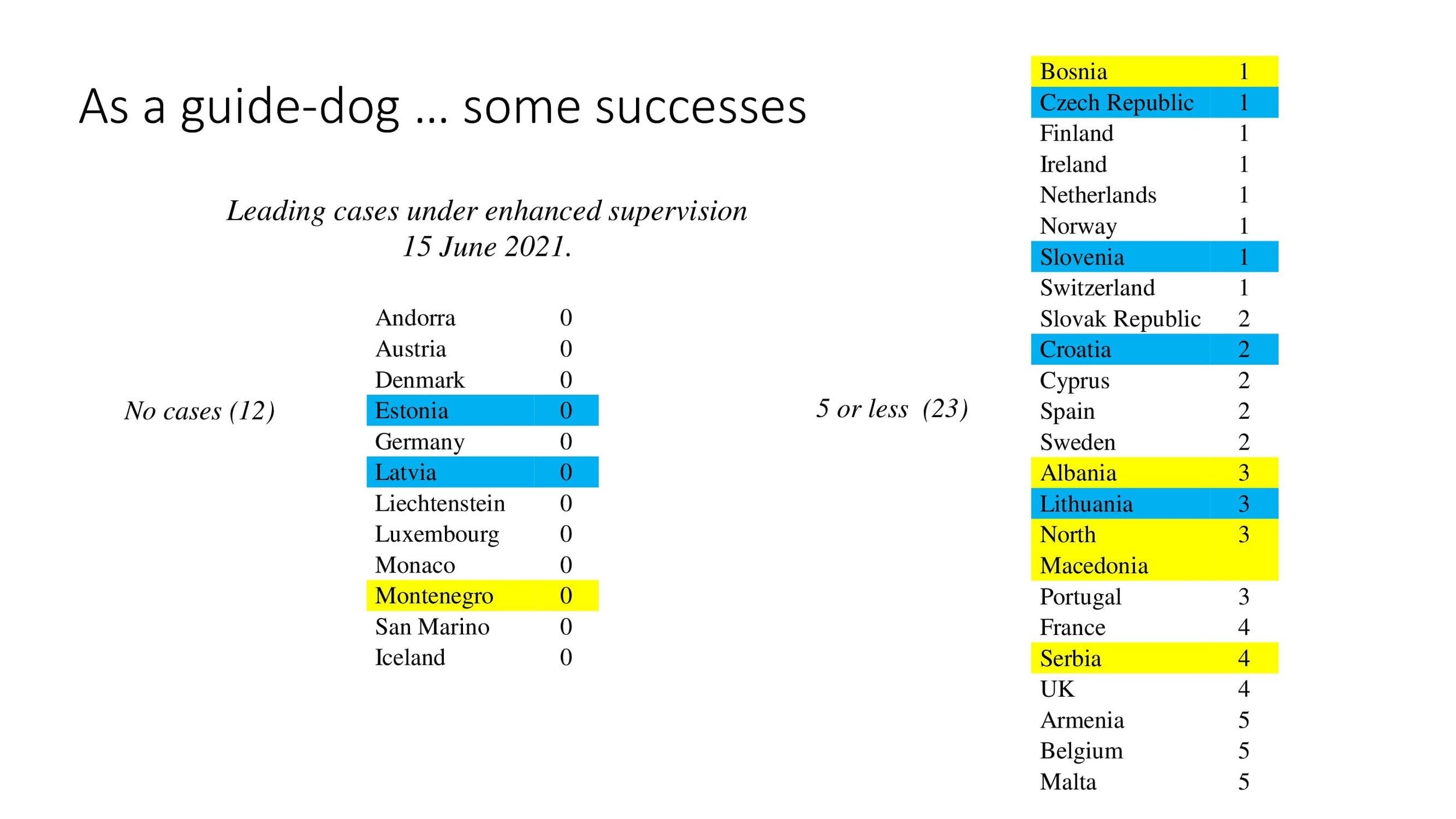

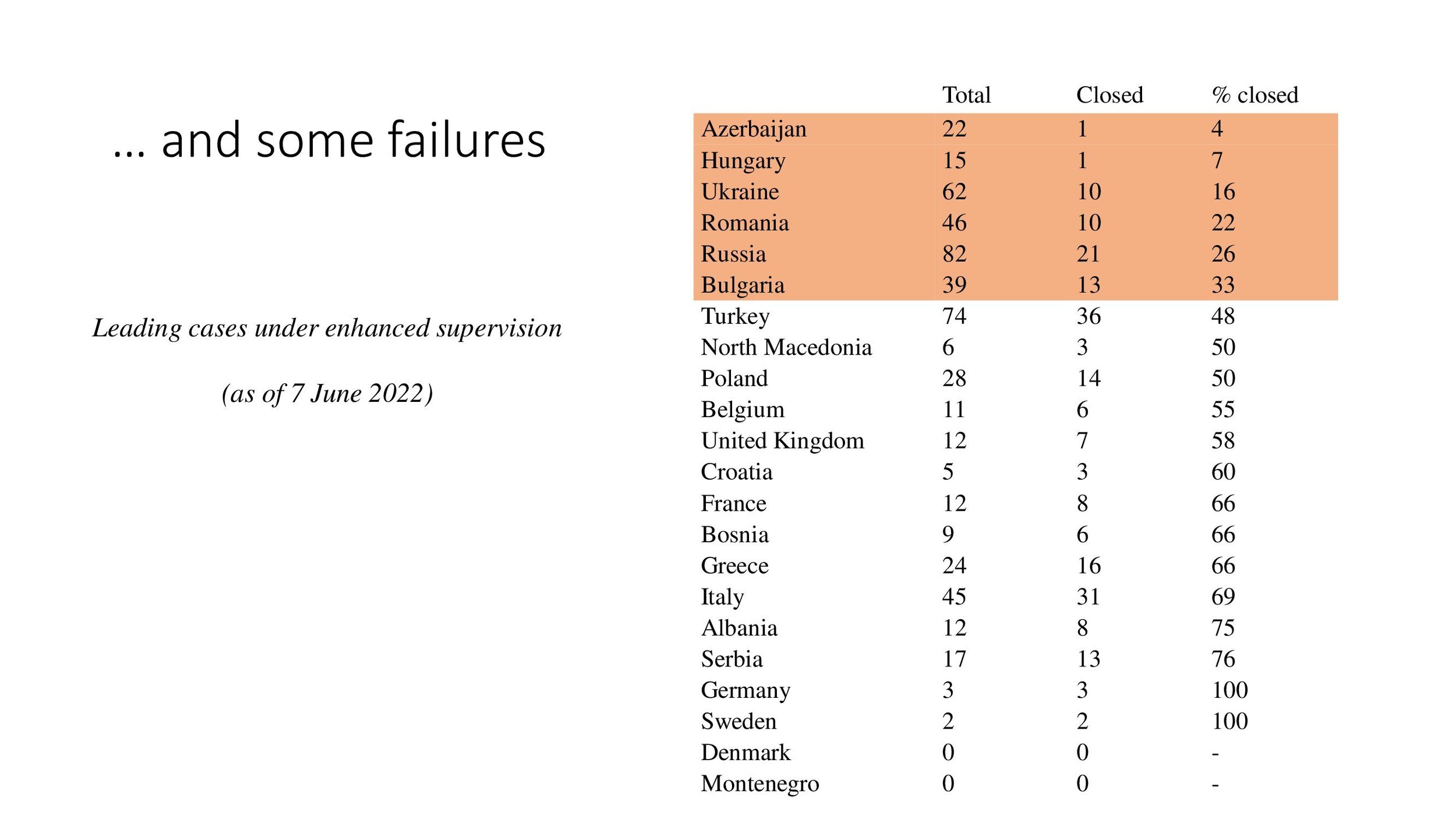

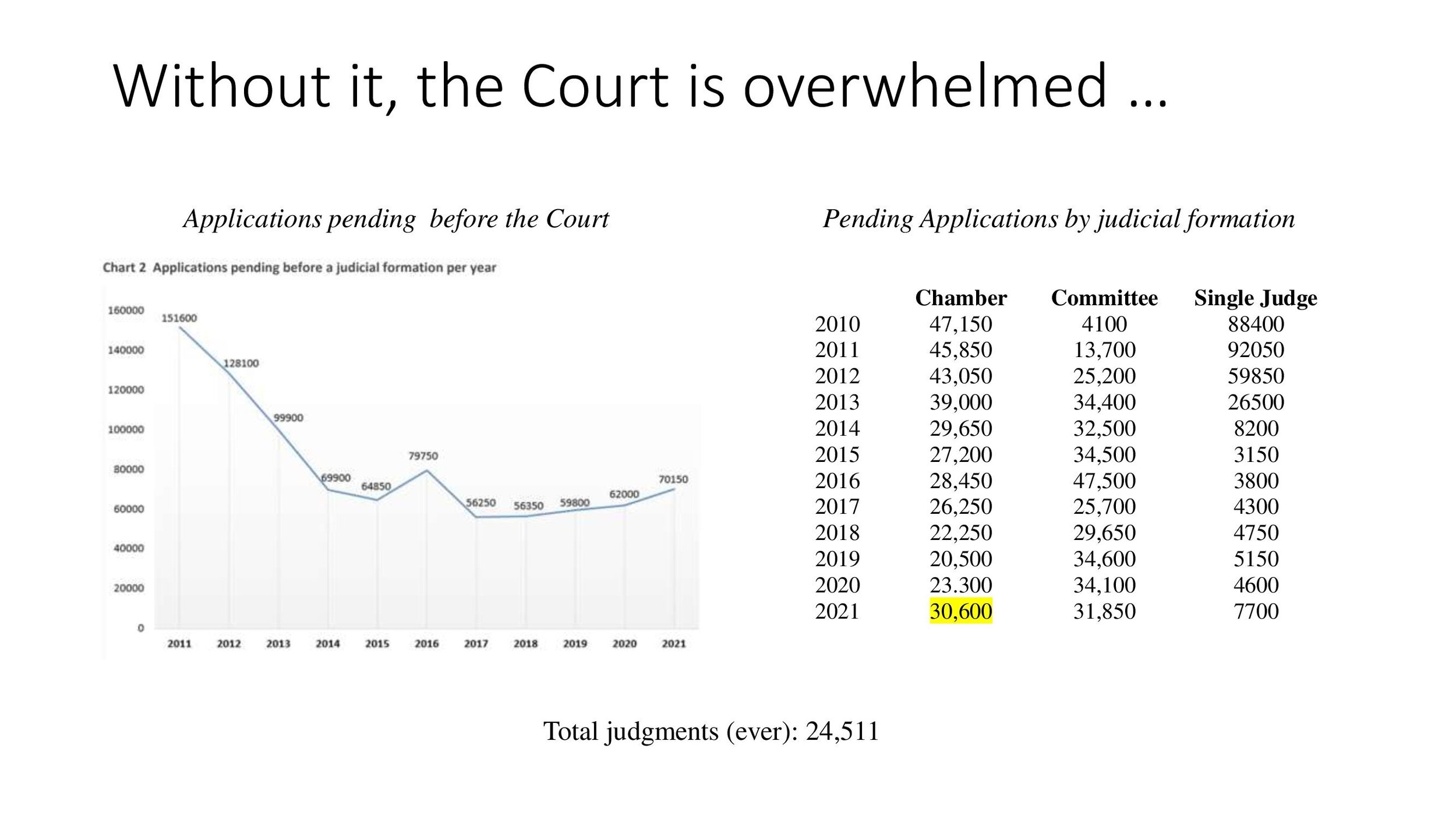

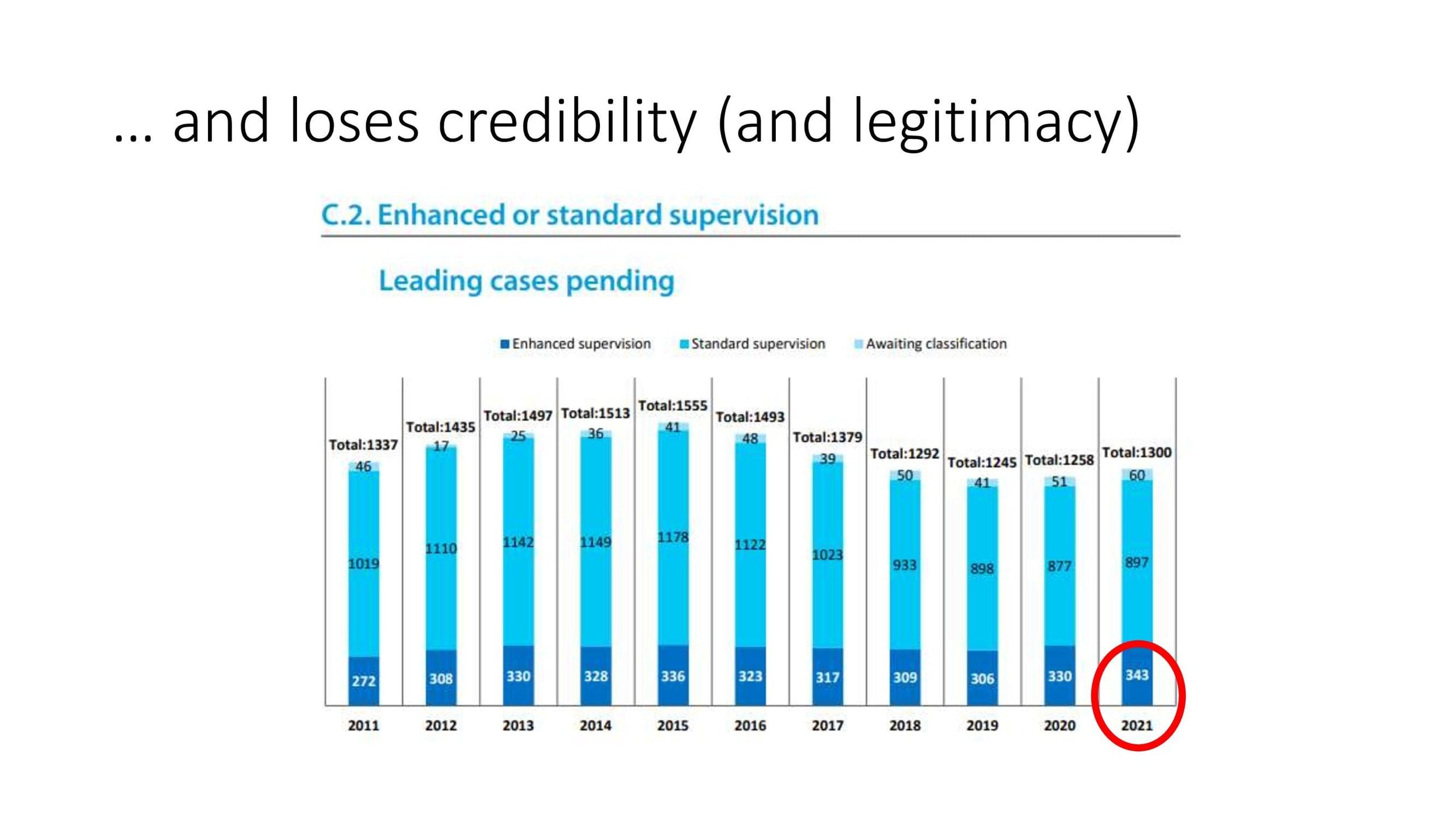

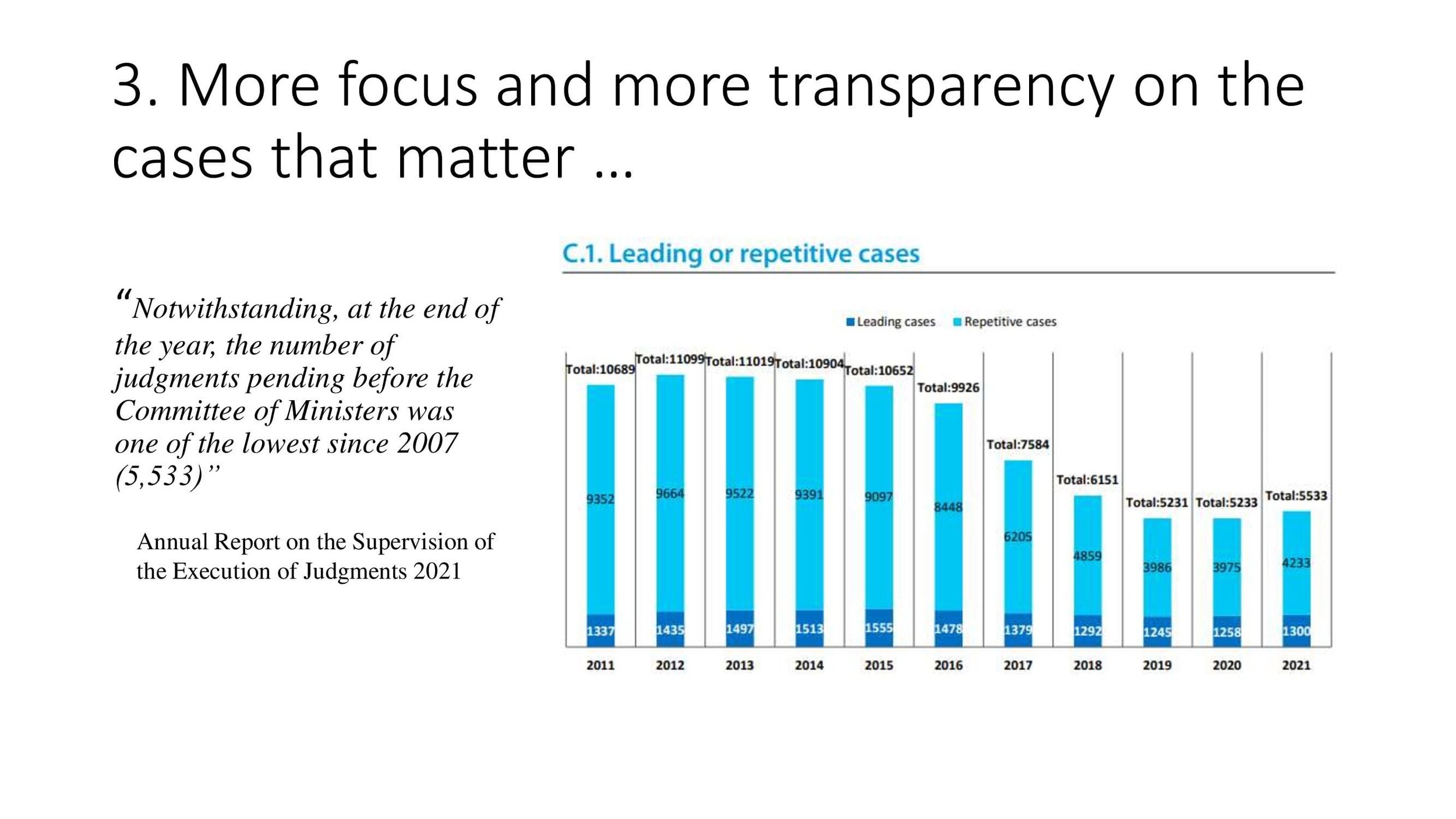

This briefing highlighted the critical problem with the non-implementation of ECtHR judgments. As of 1 January 2022, there are 1300 leading judgments pending implementation, which concern issues notably related to structural and/or systemic human rights problems. In addition, this number is rising, meaning that the problem is worsening and threatens democracy, human rights and the rule of law – and, as a result, the overall existence of the ECHR system itself.

The briefing set the scene for the non-implementation of ECtHR judgments across Europe and addressed cases involving victims of political persecution, such as the cases of Osman Kavala, Turkish philanthropist and human rights defender, and Intigam Aliyev, Azerbaijani human rights defender and lawyer. It also included a direct account of what it is like to be a political prisoner, despite having a judgment from the European Court in one’s favour, from Azerbaijani investigative journalist and former political prisoner Khadija Ismayilova. The briefing provided participants with the opportunity to gain more information on these crucial issues and discuss the best way to promote the implementation of ECtHR judgments.

The briefing was chaired by Dr. Hans-Jörg Behrens, Agent of the German Federal Ministry of Justice before the European Court of Human Rights and included interventions by Ramute Remezaite, EIN Board member, Implementation Lead at the European Human Rights Advocacy Centre (EHRAC), Khadija Ismayilova, Azerbaijani investigative journalist, former political prisoner, and Prof. Dr. Başak Çalı, EIN Chair, Professor of International Law, Co-Director of the Centre for Fundamental Rights, Hertie School, Berlin’s University of Governance.

We thank the Netherlands Helsinki Committee for co-hosting with us and the Hertie School’s Centre for Fundamental Rights for hosting the event space and everyone who was able to join us in person and online.

For those that missed the event, you can watch the live stream here: https://www.facebook.com/NetherlandsHelsinkiCommittee/videos/5959728040706274